Considering that pelvic floor disorders can cause a range of problems from pain to embarrassment, there should be no surprise that there is a link between anxiety and pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD). Although patients experiencing pelvic floor disorders may discuss their physical symptoms with their physicians, they may not be discussing any accompanying psychological distress — or even recognizing it themselves.

Understanding Anxiety and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

The Pelvic Awareness Project writes that patients with PFD often suffer in silence, thinking that symptoms such as pain and urinary incontinence (UI) are normal or that there is nothing to be done for them. These patients often feel embarrassed, but can also feel stigmatized by healthcare providers who do not take their concerns seriously. Real stories of being dismissed at medical appointments, such as this one shared by the National Association for Continence, serve as reminders to physicians just how much their advice and attention can help or hurt.

Individuals with incontinence, pain or pelvic organ prolapse experience changes to their quality of life, and these changes can lead to anxiety and depression. A literature review published in Sexual Medical Reviews found that between 50 and 83 percent of women with PFD reported sexual dysfunction, compared with 30 to 50 percent of the general population. The reasons cited for a reduced sexual experience were largely psychological - they were worried about incontinence (urinary or fecal), pain during sex, or for women with prolapse, the "image of their vagina."

A study published in BMC Psychiatry investigated whether one specific PFD — urinary incontinence — could result from anxiety and depression. This study found that in women with anxiety, the incidence of UI was 10 percent higher (27.6 vs. 37.8) than those without anxiety. In women with depression, UI was 16 percent (28.0 vs. 43.7) higher. The authors point out that while other studies have suggested a link between antidepressants and UI, it remains unclear whether antidepressants actually cause UI.

Finally, a case-control study of 100 women with PFD and 100 control group participants published in the International Journal of Women's Health found that women with PFD experienced depression symptoms three times more often than women without PFD.

Encouraging Patients to Talk Openly

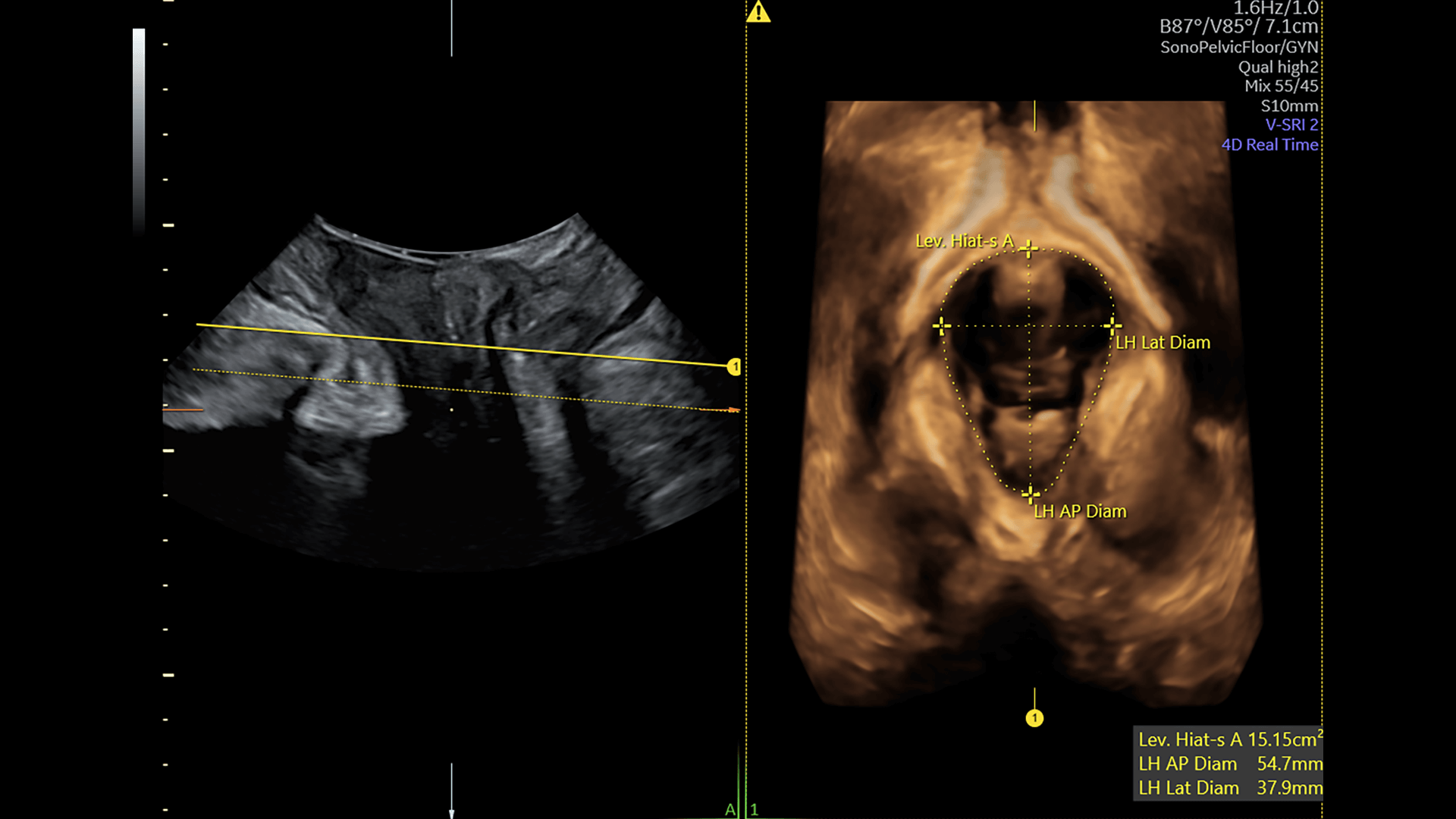

If patients are already reticent about their urological health, gynecologists have their work cut out for them when adding a conversation about mental health into the mix. A private practice gynecologist may have all the tools to diagnose the cause of pelvic pain or incontinence, but tools like ultrasound can only diagnose the physical aspects of these disorders.

Pelvic Floor ultrasound using SonoPelvicFloor, an AI-based technology that automates plane alignment, measurements, and offers a guided workflow for pelvic floor assessment thereby eliminating exam uncertainty and improving efficiency.

Learn more about imaging Pelvic Floor with ultrasound here.

Providers can and should turn to techniques described in models of holistic care to ensure they are caring for their patients' whole health. Patients may not even realize they should discuss their mental health with their gynecologist. A physician will often need to initiate any conversations about anxiety or depression related to gynecologic conditions.

Seeing as gynecologists often serve as primary care providers for their patients, it's important that they be cognizant of the reality that many of these individuals will have no other opportunity to be referred to a mental health provider.

Physicians should ask open-ended questions of patients who are experiencing PFD and affirm their concerns as appropriate. For example, a physician could ask whether a patient's incontinence has limited their activities, such as attending social events or traveling. If the patient affirms, the physician could follow with a statement like this: "I hear that from many of my patients. Does it bother you or make you feel sad when you feel you can't socialize as much as you used to?"

Simple questions paired with active listening and attention to nonverbal cues can help physicians know when additional questions may be needed. Physicians may consider using screening scales for anxiety and depression, such as these two five-question scales published by the Journal of Affective Disorders. Scales like these are quick and easily completed, and they can signal the need for a mental health services referral. It may be helpful for physicians' offices to keep a list of therapists or psychiatrists specializing in treating people with anxiety from PFD on hand, so referrals can be made on the spot.

Gynecologists need to be comfortable with teasing out whether a patient might also be experiencing anxiety related to PFD. Disorders of the pelvic floor and anxiety often go hand in hand, as PFD causes more than just physical symptoms. Remember: Patients may be reluctant to bring up issues of mental health on their own. Physicians who make a habit of always asking about mental health may find that their patients are more transparent about their health in general.