For decades, there was a gap in fertility laws relating to consent for donated sperm: In some cases where patients were told they were receiving sperm from an anonymous or chosen donor, fertility center clinicians were using their own sperm for in vitro fertilization (IVF) without their patients' knowledge.

Recent legal cases in the United States and worldwide have highlighted the lack of regulation for donated sperm and the inadequate fraud protection for patients undergoing treatment. Many states and countries are beginning to close the gap.

A Review of Fertility Fraud Litigation

Many of the instances of fraud that have now come to light happened between the 1970s and 1990s, before meticulously cataloged, cryopreserved donor sperm was widely available, but some occurred in the early 2000s.

One of the earliest court cases on fertility fraud took place in Virginia in the 1990s against a fertility doctor who used his own sperm for IVF treatments. No law specifically prohibited or criminalized his actions, though the clinician was ultimately found guilty of mail fraud and criminal obstruction for lying to investigators about using his own sperm.

More recently, a group of parents and children sued an Indiana clinic owner who spent more than a decade falsely impregnating patients, telling them their sperm samples came from an anonymous donor. Between the families' outrage at the lack of a fraud law and the eventual involvement of the Indiana Statehouse, the state passed a law making fertility fraud a felony in May 2019.

Texas followed suit with a fertility fraud bill in July. The Texas law, however, considers lying about the source of sperm a felony sexual assault because of the violation of trust in the patient-physician relationship. These laws ban any health provider from implanting human sperm, eggs or embryos from a donor the patient did not specify or consent to.

The Texas and Indiana laws are the only state laws in effect, with the exception of a California law passed in the 1990s that uses more general language and does not single out healthcare providers. Similar lawsuits for clinic owners using their own sperm to fertilize eggs are ongoing in Vermont, Idaho and Connecticut; however, with no criminal statute in those states, the suits are all civil or malpractice.

Changing Perceptions Around the World

One of the main concerns about using one person's sperm to conceive large numbers of children in a close geographic area is that those children may unknowingly conceive children together, leading to birth defects or other health concerns.

In the United Kingdom, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act of 1990 limits the number of families a sperm donor can provide samples for. The UK hasn't been immune from the same type of fraud, however: One fertility clinic owner fathered 12 known children without patient consent and possibly hundreds of others over the course of two decades.

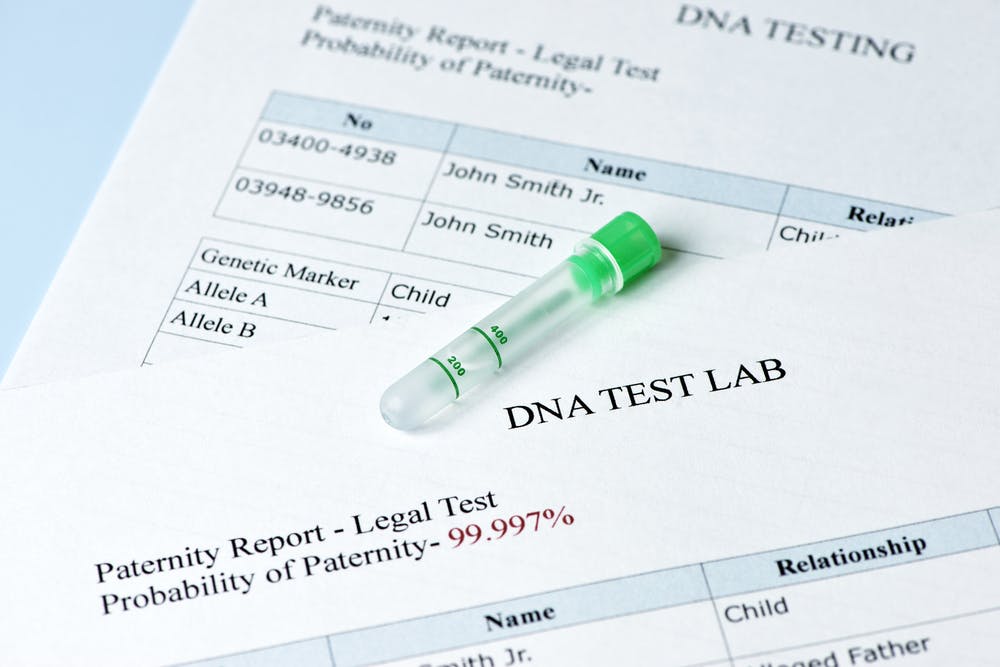

A lawsuit is also ongoing in the Netherlands, where 12 people have filed a suit against a Dutch fertility clinic alleging the director used his own sperm in place of donor samples for IVF. The director has since died, but his probable children won a victory when the courts decided they could test his DNA despite a prohibition in the doctor's will.

The lack of regulations around sperm donation and fertility fraud may stem from a basic expectation of trust between patients and doctors. In fact, many women affected by these actions never suspected anything, with most legal action coming about only after their children noticed inconsistencies in DNA tests.

Undergoing IVF is an emotional time for your patients. While patients are fighting for international change for fertility protection, the best thing any clinician can do is to ensure their patient's needs are met, their wishes are honored and they stay healthy throughout the IVF process.