The relationship between stress and fertility is hotly debated — and the research highly conflicting.

A study of 4,769 women and 1,272 men published in the American Journal of Epidemiology found that women with high stress levels were 13 percent less likely to conceive than women with lower levels of stress. However, in this study, stress did not impact male fertility. On the other hand, researchers at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (BGU) and Soroka University Medical Center in Beer-Sheva, Israel, found that 37 percent of men who experienced prolonged periods of stress had sperm with low motility. Confounding patients even more, a study published in Social Science and Medicine found that stress and fertility are not causally related: Women's stress prior to and during IVF treatments did not impact cycle outcomes. These findings held true for women regardless of their age, how long they were trying to conceive and whether or not they had been treated for infertility previously.

Regardless of what the research says, stress does cause physiological changes within the body. It boosts adrenaline and cortisol. These stress hormones, in turn, inhibit the release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). Stress also increases prolactin production.

Here is an overview of what happens to male and female fertility when stress is involved — and what reproductive endocrinologists and their staff can do to help.

Stress and Fertility in Women

GnRH is manufactured by the hypothalamus. It signals the release of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) from the pituitary gland. These hormones stimulate the ovaries to release estrogen and develop and grow a dominant follicle.

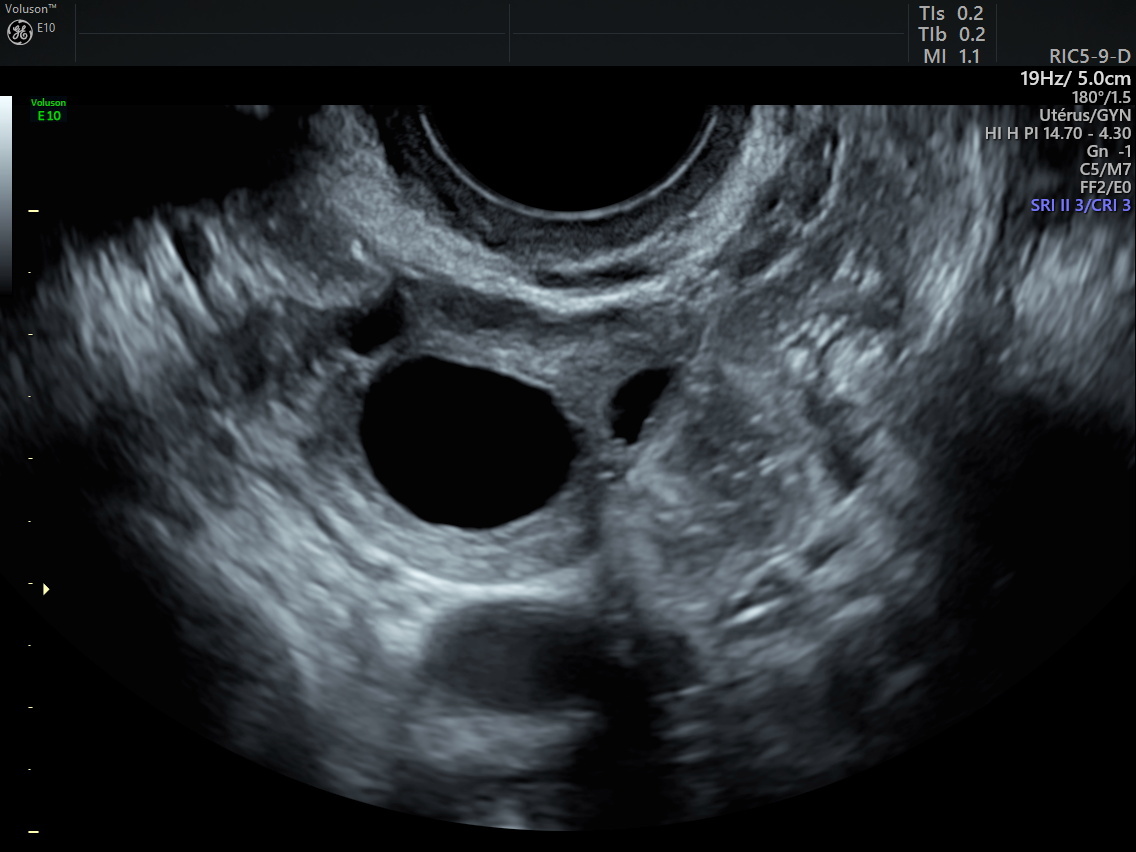

ultrasound image of ovary with dominant follicle

If GnRH doesn't trigger this process, ovulation may become irregular or temporarily stop altogether. In extreme cases, the ovaries may atrophy and cease to function.

Prolactin is produced by the pituitary gland. During pregnancy, high prolactin levels prepare a woman's breasts for breastfeeding. Following the delivery, prolactin stimulates milk production. While nursing, prolactin helps the breasts release milk. However, unless a woman is pregnant or nursing, her prolactin level should be less than 25 ng/mL. High prolactin, or hyperprolactinemia, may disrupt or inhibit ovulation. In mild hyperprolactinemia cases, ovulation may occur but result in insufficient progesterone production. Progesterone deficiency may compromise receptivity of the endometrial lining and result in an abnormally short luteal phase.

Chronic stress might also decrease libido, a condition known as stress-induced reproductive dysfunction.

Stress and Fertility in Men

Similar to the process in women, GnRH signals the release of LH and FSH to stimulate the testes to discharge androgens and develop sperm.

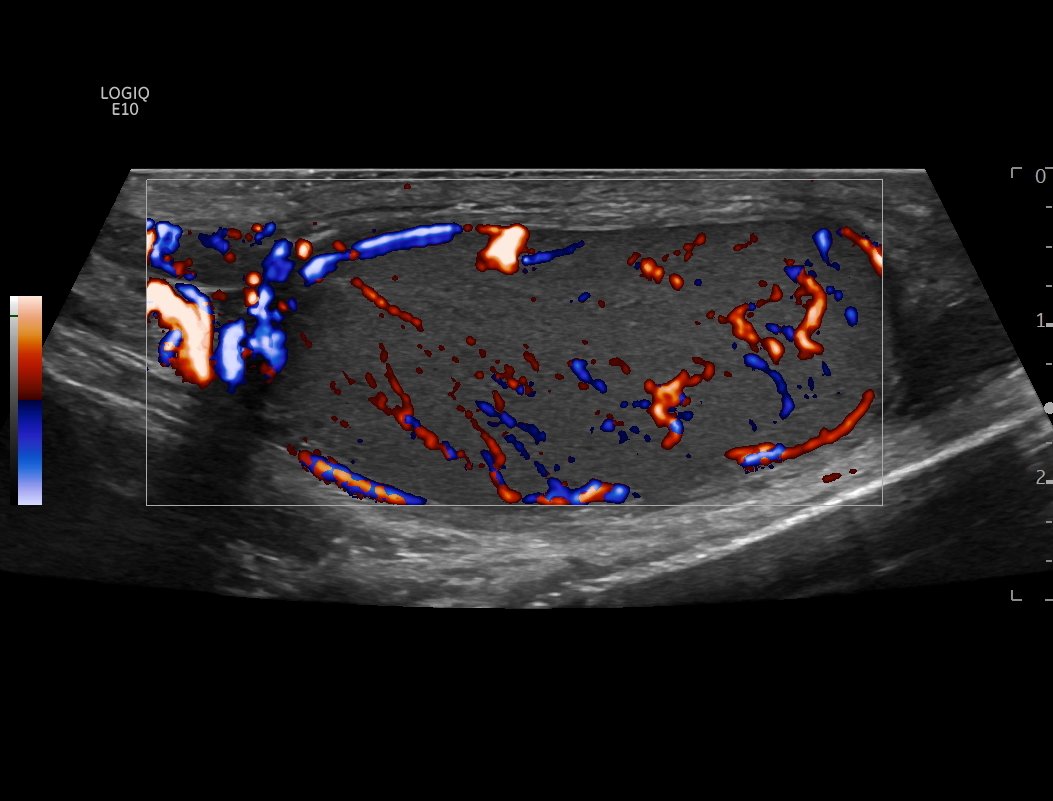

ultrasound image of testicle with color Doppler of blood flow

If GnRH doesn't trigger this process, sperm production and quality may become impaired. Again, in extreme cases, the impact may be irreversible.

Surprisingly, men also produce prolactin to help regulate testosterone and other systems and functions. In men, hyperprolactinemia (greater than 17 ng/mL) signals the testes to release less testosterone, resulting in the same effects as inhibited GnRH.

Men can also develop stress-induced reproductive dysfunction, and when ejaculation cannot be achieved, fertilization is an impossibility.

Helping Reduce Patient Stress

Particularly when stress develops into depression, women are more likely to drop out of fertility treatments — or not even start. All in all, it's in the best interest of patients and reproductive endocrinologists alike to address stress. The authors of a study published in the Journal of Psychotherapy Integration recommend incorporating psychosocial services into infertility care, with periodic screening of the patient's stress level. This is especially important after a failed treatment cycle.

If implemented, however, patients should be reassured that treatment will not be interrupted regardless of the results. Instead, they would be offered additional mental health support.

The researchers suggest that simply acknowledging and empathizing with patients, as well as providing a forum to express their feelings, may help reduce it. In other words, the medical goal of overcoming infertility and the psychological goal of continuing to participate in one's life despite infertility are complementary.

Because financial constraints are a big source of stress for patients, fertility clinics should also offer information and resources to help patients afford treatments.

Finally, a study published in the Journal of Human Reproductive Sciences found that women were less stressed when accompanied to appointments by their husbands rather than other family members. Reproductive endocrinologists should also attempt to include both partners throughout treatment cycles.

Stress and fertility may likely remain a chicken-or-egg proposition, but physicians and their teams have the power to improve patients' outcomes and mindsets.